Originally published in the October 2008 issue.

An editorial by James Hyder, Editor/Publisher

In April 1985, the CEO of Coca Cola held a press conference in New York City to announce that the company was changing the century-old formulation of its famous soft drink. The new version was officially given the “Coca Cola” name, and production of the original formula was halted that week.

The new soda, which became widely (but unofficially) known as “New Coke,” had received favorable reactions in taste tests and focus groups. But ultimately, millions of customers, angered that the company would suddenly change the product it had labeled “The Real Thing,” pressured it to reintroduce the original flavor. The company hurriedly returned it to store shelves less than three months later, re-branded as “Coke Classic.” Coke executives were widely ridiculed for underestimating their customers’ devotion to the brand and for their perceived highhandedness in tinkering with a classic.

In September 2008, Richard Gelfond, co-CEO of Imax Corporation, told members of the Giant Screen Cinema Association that “we don’t think of [IMAX] as the giant screen.” Rather, he said, “it is the best immersive experience on the planet.”

The company takes this position because it has chosen not to differentiate its new digital projection system in any way from the 15/70 film systems it has been installing in giant-screen theaters since 1970. This despite the fact that, according to Imax VP Larry O’Reilly, its two major digital partners, AMC Entertainment and Regal Entertainment Group, both originally wanted to brand the new screens as “IMAX Digital.” And based on the reaction Gelfond’s announcement received in New York (and on many conversations I’ve had since) many, if not most, institutional IMAX operators would prefer this as well. In short, virtually all of Imax’s customers and partners would like to see a distinct new identity for the digital system.

But Gelfond flatly rejected this possibility, offering an absurdly flawed analogy with BMW automobiles. He said that the German carmaker offers the 7-series line of larger, more powerful, luxury models as well as the smaller, entry-level 3-series cars. “People don’t say ‘The 3 isn’t a real BMW because it’s smaller.’”

Of course, this ignores the fact that the model numbers, to say nothing of the prices, clearly distinguish BMW’s different product lines in consumers’ minds, while maintaining the unity of the brand. No car buyer believes he has bought a $125,000 760Li only to receive a $30,000 328i.

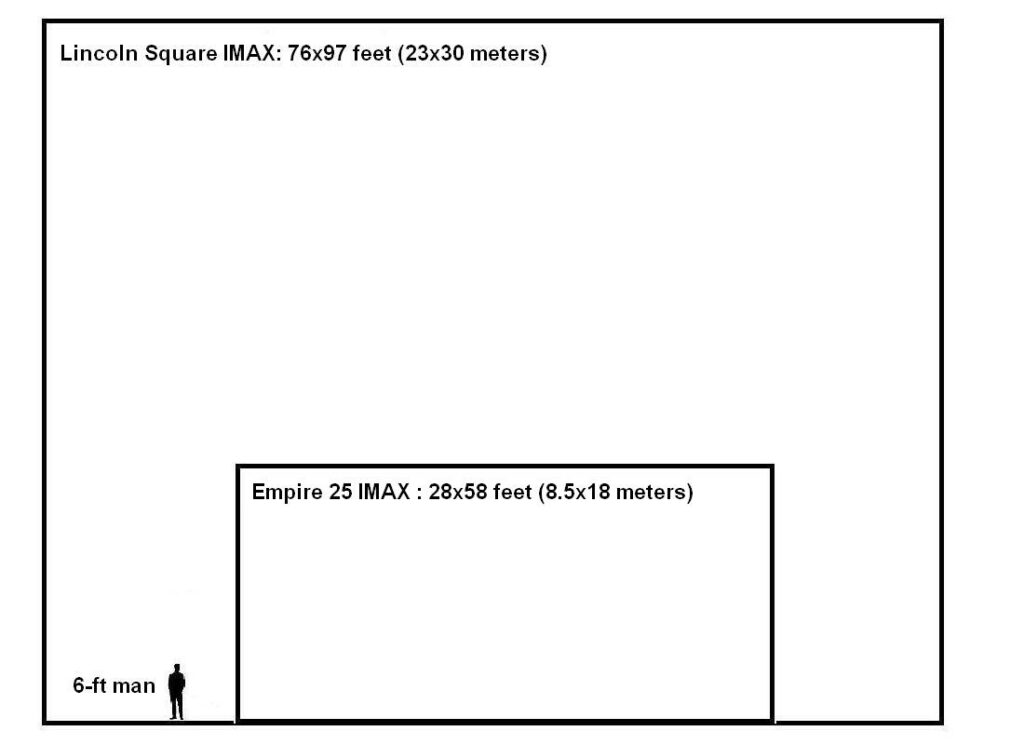

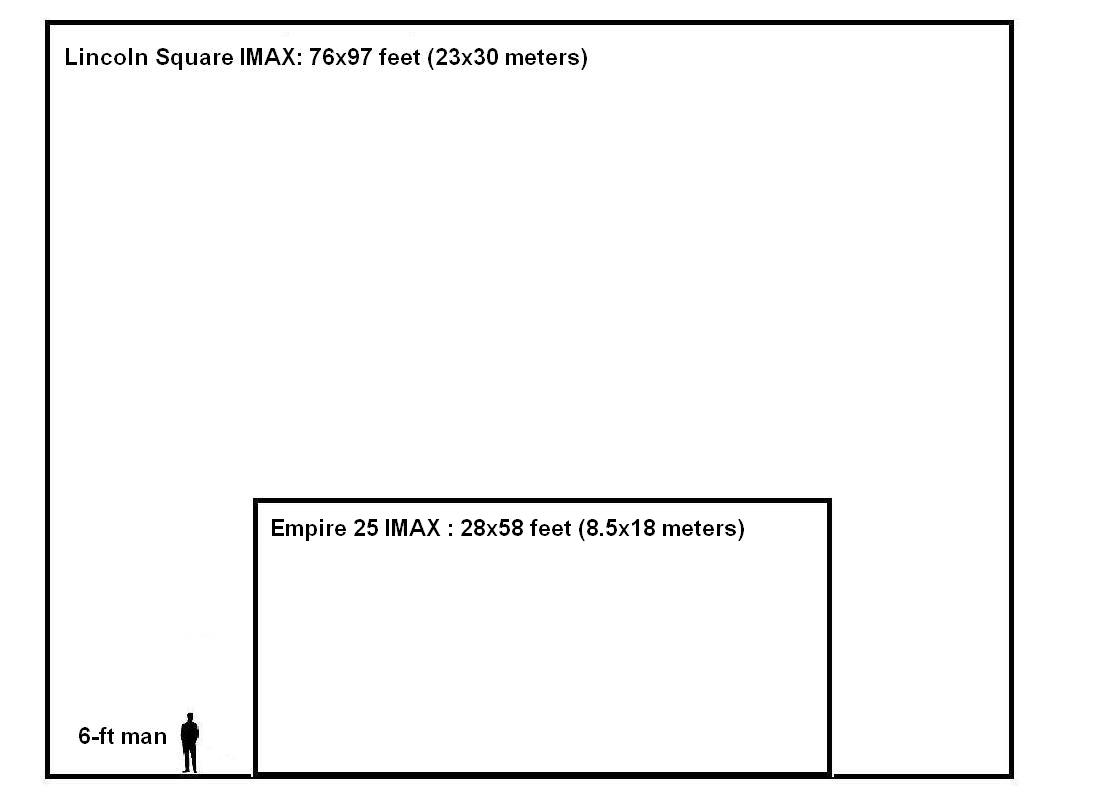

Yet this is the position in which Imax is now putting customers who pay $15 to see films at (for instance) New York City’s AMC Empire 25 IMAX digital theater, with its 28×58-foot (8.5×18 meter) screen. They see the IMAX name on the theater and have no idea until after their ticket has been torn and they walk into the auditorium that that screen is about the same size as the one in the adjacent 35mm auditorium, and less than a quarter the size of the one in the AMC Lincoln Square IMAX 15/70 theater, 26 blocks away. The screen in the older film theater is 76×98 feet (23×30 meters). Here’s a graphic representation of the difference:

Gelfond explained that the company feared an “IMAX Digital” brand might cast the older film-based theaters as “second-class citizens” in the public’s mind, since “digital” generally has connotations of “newer,” and “cooler.”

Although this apparent concern for museums and other “old school” operators is touching, it seems far more likely that the company was worried that ticket buyers who noticed the difference between the average 4,800 square-foot (450 square-meter) 15/70 film screen and a digital one 1,250 square feet (120 square-meters) in area wouldn’t return to the smaller if they could see the same movie on the larger.

In other words, “IMAX Digital” might become the next “New Coke.” Widespread public preference for the “classic” experience would harm Imax’s return on the tens of millions of dollars it is investing in the 170+ joint venture deals it has signed.

The “wow” factor

Gelfond claimed that the company only puts IMAX digital systems into multiplex auditoriums that meet certain criteria. He jokingly said, “It’s a very scientific test. It’s called the ‘wow’ factor. So if you don’t go in and go ‘wow,’ we won’t do it.”

In more than 24 years in the business, I have personally been in 132 giant-screen theaters of all brands, formats, and sizes, including four MPX (15/70 film) theaters and five IMAX digital screens. I may be jaded, but none of those nine coaxed even a faint “wow” from my lips, because all were merely ordinary multiplex houses that had been modified slightly. The seating rake was unchanged and nowhere near the 20–25-degree angle that is standard in purpose-built IMAX theaters. The room’s depth, from the screen to the last row, may have been reduced slightly by moving the screen forward and removing a few rows of seats. But most were still significantly deeper than the width of the screen, thus providing the audience a narrower (i.e., less immersive) average field of view.

But most importantly, of course, the screens were only a fraction of the size of a “real” IMAX theater screen. And all were shorter, 1.9-aspect-ratio screens, not the tall 1.44 screens of classic IMAX theaters. And let’s face it, the biggest aspect of the “wow” factor is height. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to see that even a very wide screen is not nearly as impressive as a one that towers six or eight stories high.

The screen door effect

Using two high-powered digital projectors, the IMAX digital system projects an image that is bright, with good contrast and slightly better resolution than other digital projectors. But every IMAX digital theater I’ve been in has also had a noticeable “screen door effect,” that is, a visible dark grid pattern separating the pixels. It is particularly noticeable in lighter image areas, and is less visible the farther you are from the screen. But even with my 53-year-old eyes, I was able to see it from the front half of most of the five theaters I’ve been in. If you move back to eliminate the pattern, your field of view becomes narrower, and hence no different than an ordinary movie theater.

At the New York demonstration, I was seated in the fourth row next to a long-time IMAX theater manager. I had not said anything to him about my perceptions of the IMAX digital theaters I had already seen. But the moment the first image came up on the screen — it was the MPAA rating card for the first trailer — I heard a gasp as he noticed the screen door pattern that made the card’s white-on-green text look “jaggy.” He later confirmed being stunned at how obvious and distracting the pattern was.

Although many people I spoke with after the demo shared this reaction, to my surprise not everyone found the pattern as noticeable or distracting as I had. Some didn’t see it, others did, but didn’t mind it as much.

But for me it is clearly the biggest reason to say, “This is not IMAX.” I grant that the image is bright and contrasty, and has good color. And it only took hearing a shuttle launch in Space Station 3D to know that the new sound system is fully up to IMAX standards. I might even be willing to compromise on the aspect ratio.

But IMAX — real IMAX — presents reality. Not reality as seen through a screen door.

And even though it beats conventional 2K for brightness and contrast, IMAX digital is not, in my opinion, better than Sony’s 4K SXRD system. At ShoWest in Las Vegas last spring, I saw 21 in 4K on a screen that was at least 60 feet wide, maybe bigger. I intentionally took a seat less than one screen-height from the screen, right next to David and Patricia Keighley, as it happened. I found the Sony’s image to be bright, contrasty, and sharp, and as good or better than film would have been at that size. And most importantly, I couldn’t see any pixels or patterns.

Conclusions

Let me make one thing clear: I am not opposed to digital projection in principle, or to the IMAX digital system in particular. I think the change to digital projection in the giant-screen world is inevitable. And I fully admit that the IMAX digital system is superior, in certain respects, to some other digital systems.

But I object when anyone claims that two patently different things are the same. Where I come from that’s known as “lying.” And call me naïve, but I don’t believe that any company whose business plan is based on deceiving its customers can succeed with that strategy for very long.

Imax Corporation, whose very name means “image maximum,” has spent four decades persuading the public that that name is synonymous with “big,” with giant screens, with an experience that is completely unlike that of conventional multiplex cinema.

If, for perfectly understandable business reasons, Imax now has to move into those smaller screens, let it distinguish this new product from the other screens in that theater, as a “premium multiplex experience,” as Sydney’s Mark Bretherton has suggested.

But expecting the ticket-buying public to believe that that experience is identical to one on a screen three or four times larger is insulting. People who have been to a true giant-screen theater will realize they have been misled, and will be disappointed, if not angry. Those who haven’t will wonder what the big deal about IMAX is, and will assume that any real giant-screen theater they come across in the future has nothing better to offer and perhaps never will have the real IMAX Experience.

By not distinguishing between two different products, Imax has degraded its brand with all customers. And far from protecting the film-based theaters from second-class status, it has lowered the public’s perception of all IMAX theaters. This has even led some theaters in the institutional segment to consider dropping the IMAX brand from their marketing and perhaps even their signage. When your oldest customers want to disassociate themselves from your brand, something is wrong.

The tragic irony is that, forty years after Imax Corp. started trying to persuade Hollywood to shoot with IMAX cameras, the success of Chris Nolan’s The Dark Knight, the first to do so, has finally encouraged several other directors to follow suit. Three or four coming films may incorporate 15/70 footage. And yet, by the time these movies open, the majority of IMAX theaters may be digital screens with 1.9 aspect ratios that make the dramatic transitions in resolution and image size all but invisible. What a waste!

The lesson from Coca Cola is clear: Although the “New Coke” incident was initially perceived as embarrassing to management, the company’s reputation was ultimately enhanced by its prompt response to customer concerns. With two distinct products, “Coke Classic” and “New Coke,” sales rocketed and the company regained the top market position it had lost to Pepsi years earlier. It has remained number one ever since.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.